Quakers and the Underground Railroad

Perilous journeys for fugitive enslaved peoples

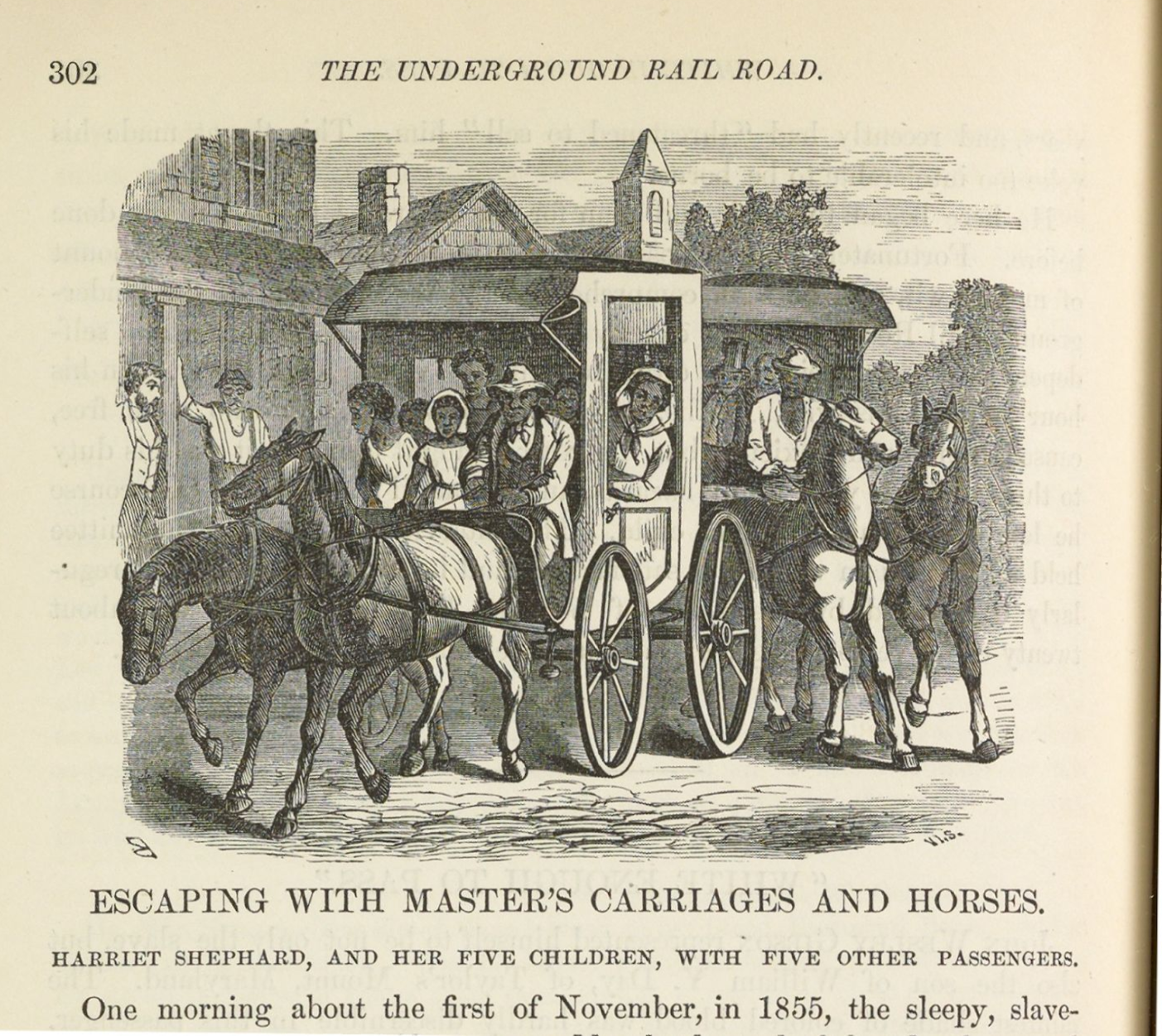

In 1855, slave Harriet Shepard escaped from Chestertown, MD, with her five children. She may have been helped by a freed black man and an enslaved man, but the group was definitely

aided by a Kent County Quaker and then by Friend Thomas Garrett, who helped them to hide in Wilmington and then travel to Kennett Square, Pa. where Longwood Meeting members cared for them. They were then moved to a Quaker family in Pocopson; from there ultimately to the Quaker-owned Vickers Tavern in Lionville to Quaker abolitionist, GraceAnne Lewis in Kimberton. There it was decided that the group should split; some went to Friend Elijah Pennypacker in Phoenixville, others straight to William Still, the free black man who ran the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia. Still wrote that part of Harriet's family went to New York City. It's unclear what happened to Harriet herself--she may have gone to Elmira, NY and possibly Canada. At any rate, her family's journey demonstrates the complex coordination of

Quakers and African-Americans in facilitating the escape.

Imperfect Allies

Quakers believe that there is that of God in each person and also, that to be whole spiritually, they need to live their beliefs. Friends recognized the equality of women quite early but were

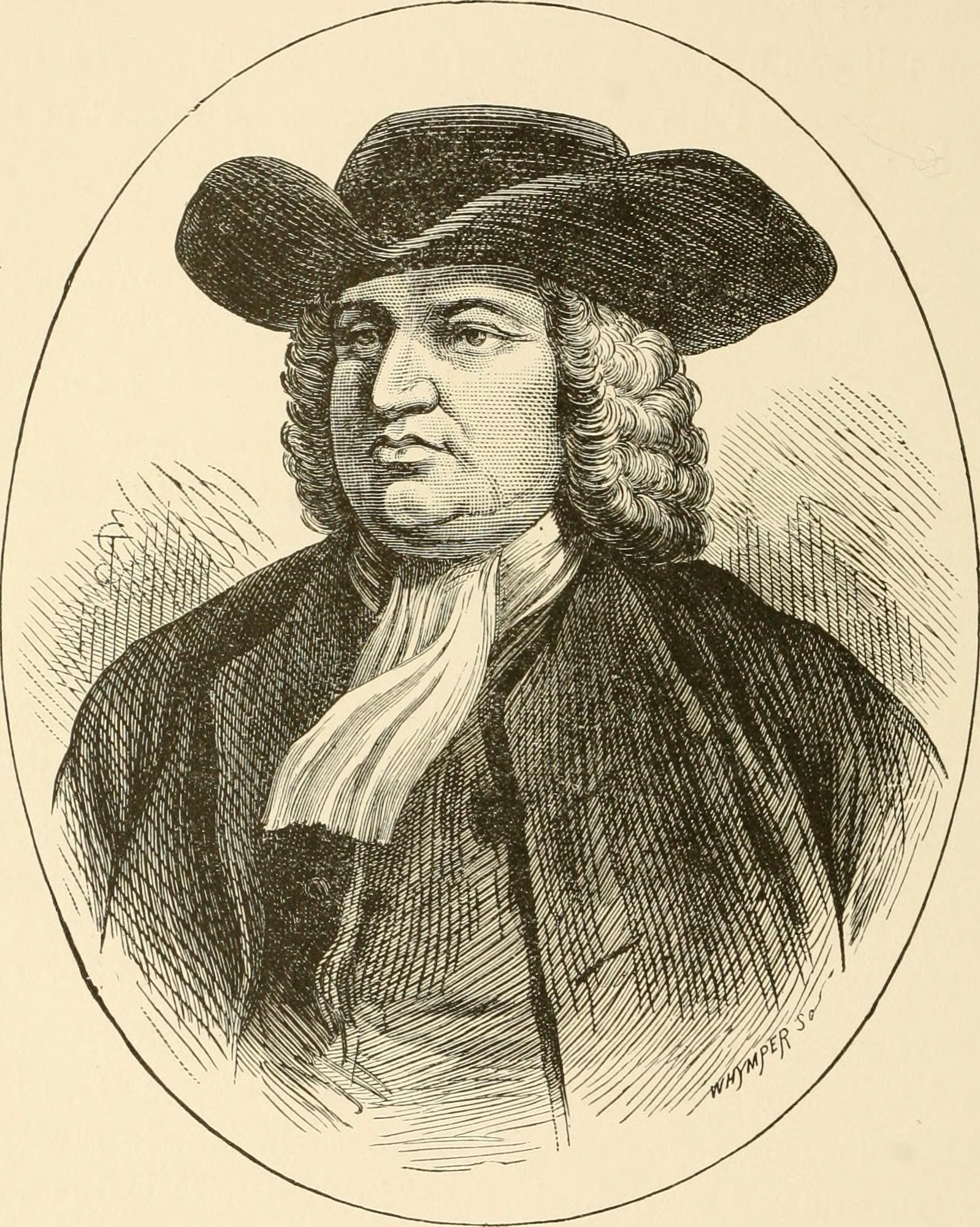

slower to recognize the evils of slavery. (Faith and Practice, p. 75) Although Quakers, including William Penn, owned slaves in the colonial era, the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) was

the first group to condemn slavery. In 1688, Germantown Quakers declared in writing their opposition to slavery. In 1753, the Friends Book of Discipline stated "let us make his [the slave] cause our own" and in 1754, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting declared to its members that "To live in ease and plenty, by the toil of those whom violence and cruelty have put in our power, is neither consistent with Christianity nor common justice." Furthermore, from the beginning of the Religious Society of Friends, members had to address the illegality of their sect in England.

Their leaders asserted that, when religious duty came into conflict with the law of the land, it was the duty of the Christian to suffer rather than obey. In 1846, American Quaker William Jackson, stated: "no one is under any moral obligation to hand himself as a tool for the commission of a crime, even when commanded by his government to do the wrong." So,

although generally sober and law-abiding citizens, many Quakers put conscience above legal duty. Certainly, it was common for slaves to advise each other: "Aim for a free state and settle among Quakers." Even if they were not the leaders of a clandestine network, Friends were unlikely to turn a fugitive into the authorities.

Seal of Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, 1800

Philadelphia had an active and quite open network of Underground Railroad operatives. Although African-Americans, such as William Still and Robert Purvis, led the effort in the city to help escaping fugitives, a few Quakers assisted these efforts. James and Lucretia Mott and

Isaac Hopper helped runaways as did a number of members of Germantown Meeting. There is a story published by his biographer, Lydia Maria Child, that Hopper rode a horse from

Philadelphia to Gloucester Point, New Jersey to intercept a ship carrying a free Negro boy and with difficulty, rescued him. The Johnson House on Germantown Pike, owned by a large

Quaker family, is documented as providing shelter, food and clothes to fugitives.

The illustration to this French edition of Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe depicts Eliza and George seeking help from two Quakers.

Quakers portrayal as heroic figures was exaggerated

That said, most Friends, like most northerners, were not involved with the organized assistance of fugitive slaves from the South. The myths surrounding the "Underground Railroad" are many, usually characterizing the escape of slaves to be widespread (as many as a million!), involving a tight network of agents ("conductors"). organized to aid them. The houses where they were hid ("stations") supposedly contained tunnels and other hiding places for the fugitives, who were guided by codes in quilts and songs. Quakers are often portrayed as heroic figures in this melodrama. Secret compartments, along with the quilts, are 20th century myths and the image of Quaker conductors on the Underground Railroad exaggerated.

Did Merion Meeting have a role in the Underground Railroad?

The reality is that a total of perhaps 1000-5000 slaves escaped the South between 1830 and 1860 and these fugitives generally relied on their own resources. Their helpers along the way

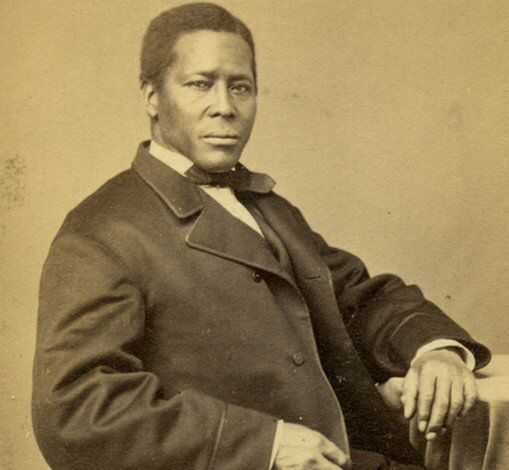

were more likely free blacks than whites, even Quakers. There was no nationwide conspiratorial network, no centralized organization. The actions of those who aided runaways were usually not secret but open: for example, Thomas Garrett in Delaware and William Still in Philadelphia were well-known agents. Garrett, at his trial in 1848 admitted everything but said to the judge: "Judge, thou hast not left me a dollar, but if anyone knows of a fugitive who wants a shelter and a friend,

send him to Thomas Garrett and he will befriend him." There certainly were people who helped fugitives, but it was smaller and more haphazard than the popular version.

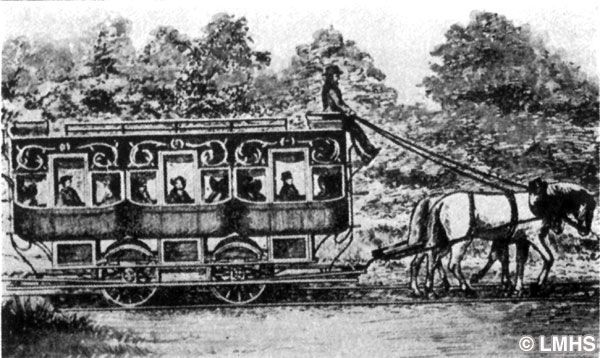

For southeastern Pennsylvania, the route of escape on the UGRR ran from MD and VA to York, Columbia or Harrisburg, then east to Philadelphia. Although the railroad in front of Merion Meetinghouse (the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, which operated from 1832 to 1850) was a conduit for runaway slaves from Lancaster County, there is no evidence that members of this meeting aided the fugitives who passed through the township on the 8-9 hour trip to Philadelphia. William Whipper, a free black man who shipped lumber to the city, sent runaways in a false end of a box car to William Still of The Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. After the

Civil War, Whipper contributed to Still's book, noting that he had sent fugitives "to you in our cars to Philadelphia."

William Still, who ran the Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia, was responsible for the delivery of fugitives through Philadelphia to New York City and beyond.

Local Legends

There are legends about safe houses in the township, but most of the verifiable activity took place not in Lower Merion but in Lancaster and Chester (called the most enlightened county in the state by anti-slavery advocates) Counties. There was also a network in Norristown. According to historian Christopher Densmore, Underground Railroad activity required a place of safety, meaning a significant minority of anti-slavery residents and a significant African-American population. In areas with few blacks and few Quakers, there was less likelihood of a network for aiding runaways. At 8% of the total population, Chester County had the highest percentage of black residents of any Pennsylvania county in 1860. The Quakers of that area were also very involved in the anti-slavery movement and in the Underground Railroad.

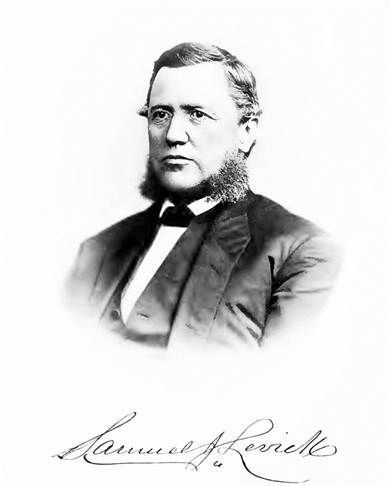

Still's notes on his work with the Underground Railroad listed young Merion Meeting member, Samuel J. Levick, as a member of the first Vigilance Committee in 1839-40. Samuel kept a diary, in which he frequently recorded anti-slavery sentiments, but prudently omitted reference to aiding fugitive slaves. Resolutions were more characteristic of Quaker abolitionism than the UGRR. Anti-slavery meetings, financial contributions, food and clothing collections, weekly sewing groups to make clothes for fugitives, bazaars and fairs to promulgate anti-slavery sentiment and raise money for that cause were typical of Quaker activism of this era.

Quakers were not united towards aiding fugitive slaves

Not all Quakers were Mott or Hopper or Garrett; in fact, most played no active role in the Underground Railroad at all. In the aftermath of the Fugitive Slave Act, Quakers had a dilemma: supporting liberty for slaves meant the perversion of union and possible violence (a clear violation of the Peace Testimony). While the PYM Book of Discipline admonished Friends not to obey the 1850 law, the Underground Railroad was not popular with gradualist Quakers, because it represented the subversive potential of the abolitionist movement. The Quaker newspaper The Friend denounced the anti-government implications of the abolitionist

movement: "It is not our place to invite slaves to run from their masters".

When Elijah Pennypacker spoke in his meeting in 1848 to say that Friends had sacrificed their commitment to God's higher law by not aiding fugitives, he was told to sit down and be silent. Not only was active resistance (civil disobedience) dangerous but secretive and illegal and sometimes led to violence (as in Christiana in 1851, when the killing of a slave owner trying to apprehend his runaway slaves led to supportive Quakers being put on trial).

Abolitionists were seen by many Friends as dangerous agitators; Levi Coffin of Cinncinati helped 2000 slaves escape, but he was not popular among conservative Friends. Fears of armed violence made support for Underground Railroad unpopular. For many Americans of this era, the tension over runaway slaves raised fears of slave revolt and slaveholder reprisal. Isaac Hopper was disowned by his Meeting in 1842 and Lucretia Mott was threatened with disownment in 1842, 1847, 1848 and 1850.

The Underground Railroad was more important in the verbal battles that led to the Civil War, with the South claiming to have lost 1000 slaves each year. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 had little to do with recovering fugitives; it was more about the sectional struggle for power. Those who escaped into northern states were unlikely to be pursued; perhaps as many as 200 fugitives were remanded to slavery between 1850 and 1861. Runaways held dramatic value for both the North and the South. The northern strategy was to make the slave south believe that more were escaping than were and southerners were likewise inclined to enlarge the numbers of fugitives to enhance their grievances against the North. Both sides had reason to exaggerate.

Related History Pages

Related History Pages

View more