Quaker Families and Children in Early 19th Century America

Separation of the spheres

(house and workplace) that accompanied the early industrial revolution, the family changed from an economic unit to a social refuge. The home became almost a sacred place for middle-class Americans. For Quakers the importance of family in raising children was not new, but key to 19th century efforts to sustain the Religious Society of Friends while improving the world. The belief that the Inner Light dwelt in every person influenced child-rearing methods. At the same time that the family was the main institution for raising children, the Meeting also played a role in shaping families.

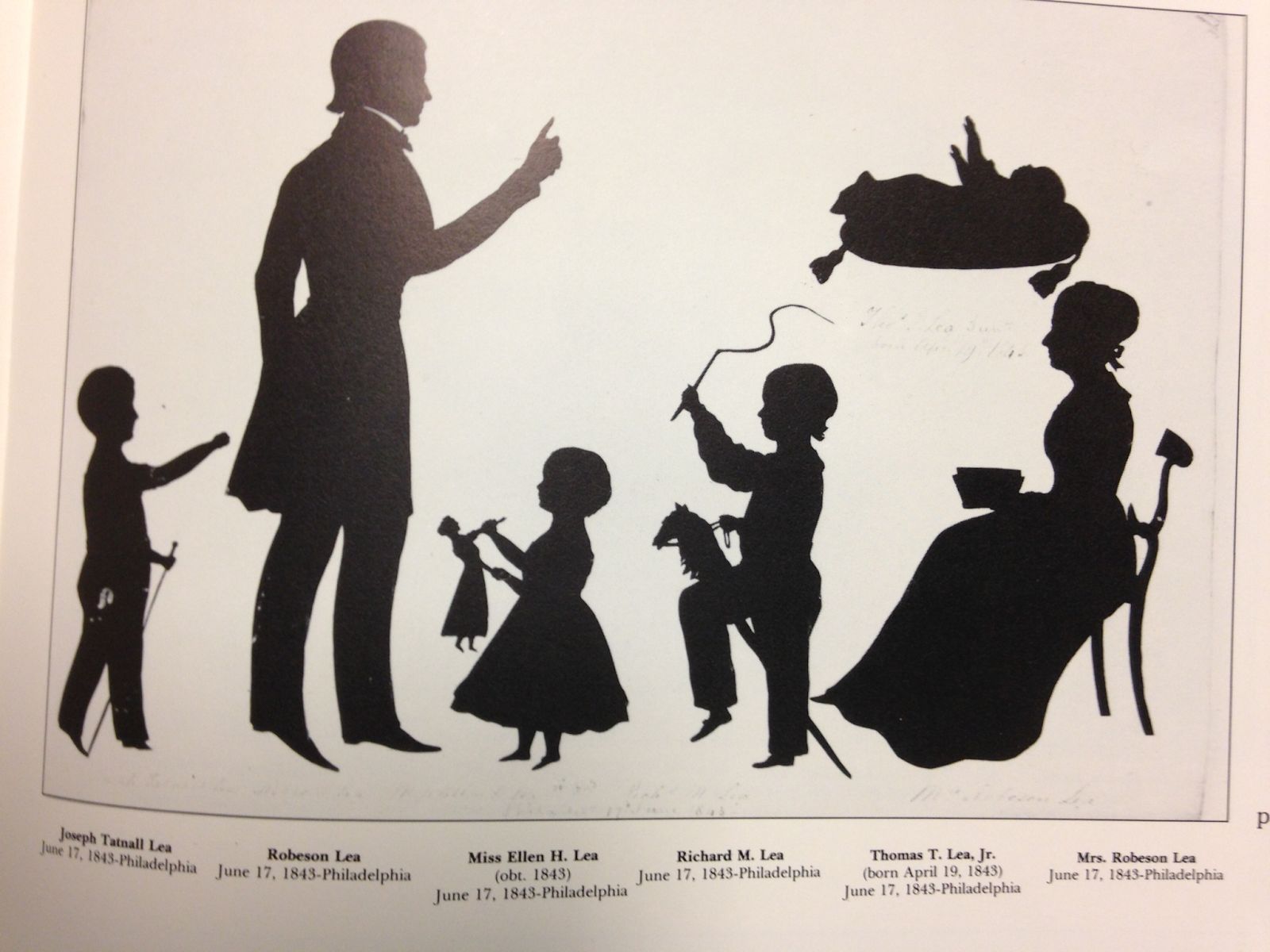

Quakers were early leaders in this “cult of domesticity” which came to dominate American culture in the 19th century. In this popular middle-class view, the home was the center of communal life and mothers were the main promulgators of moral and spiritual education. Perhaps because female members of Quaker meetings were treated as spiritual equals to men and had their own meetings-for-business, which focused on the concerns of families, Quaker women were early adopters of the view that the family was the key institution for raising children. At the same time, across American society, the nuclear family was gaining in

importance (by 1810 27% of portraits were of nuclear families) and children were not just workers. The relationship between parent and child was more equitable; middle class children were going to school; and clothes and furniture were being produced just for children. Gentle

child-raising was becoming the norm.

In many ways Quaker families were not much

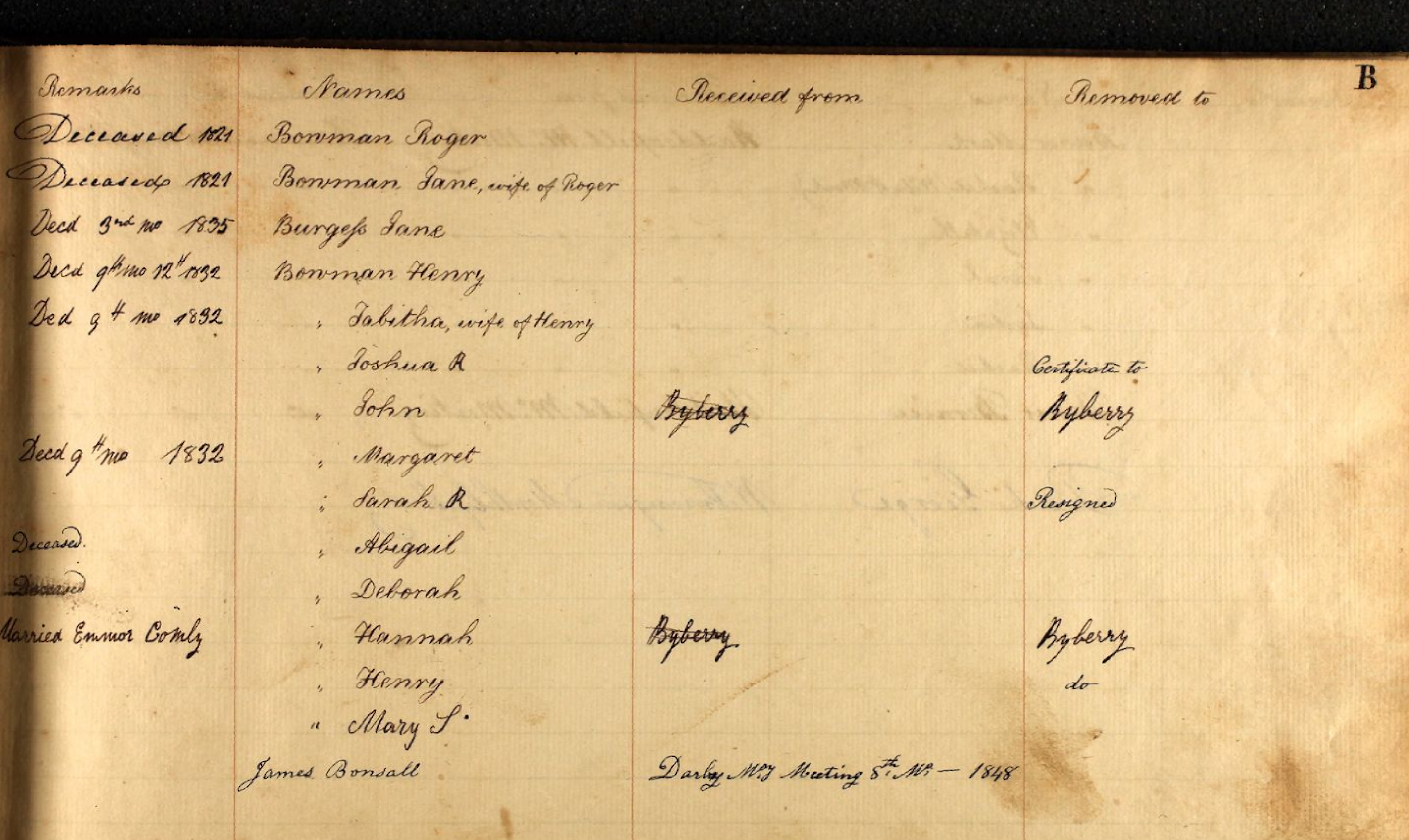

A page from the Burial Record of Merion Friends Meeting, showing the Bowman family in 1832 and their heavy familial loss.

different from their non-Quaker neighbors in the early nineteenth century, when farms were still the predominant feature of the Lower Merion landscape. In 1850, the United States census showed 613 families and 195 farms in the Township, many of the latter owned by well-off Quakers, including Merion Meeting members, Isaac W. Roberts ( whose farm was valued at $15,000, Edward Price ($13,000) and Jonathan Jones ($7000).

Among Quakers at this time, the average number of children per family had declined to 5.3, a slightly smaller number than the nationwide average of 6-9. There were local exceptions; the Bowman family of Merion Meeting boasted nine children when their parents (and six of them) died in the cholera epidemic of 1832.

Although since its beginning, the Religious Society of Friends was less dependent on the meeting and the school for the education of children than other sects such as the Puritans, there

was a significant degree of community involvement in the decision to marry and Quakers expected their members to marry within the society. The Friends Book of Discipline of 1856 explained that the Monthly Meeting’s involvement in marriage was “in order that Friends may

extend a watchful eye over their members” and, more specifically, “to discountenance mixed marriages... because... difficulties and embarrassments are liable to ensue in the education of children.”

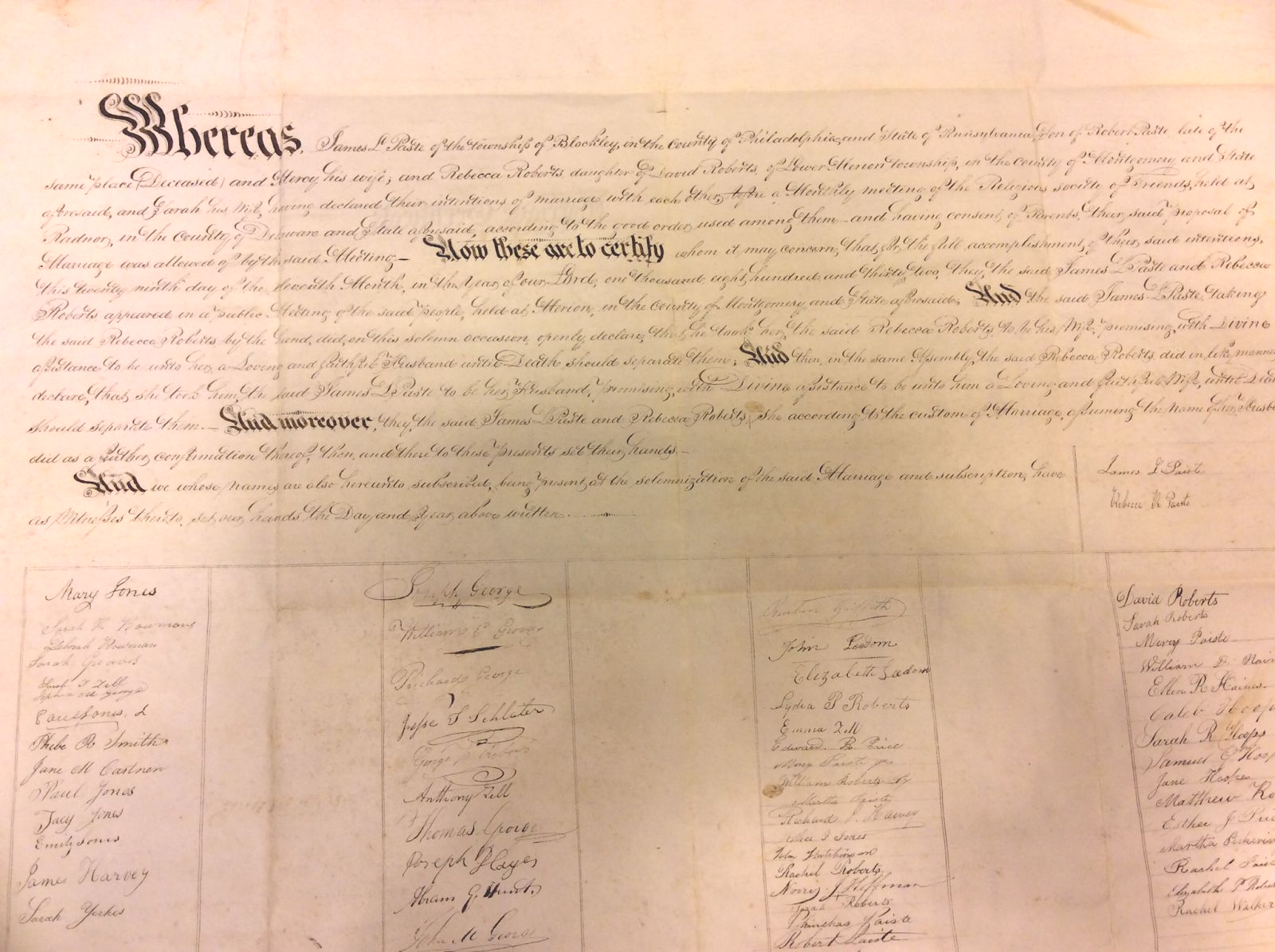

The Quaker marriage procedure

began with the application by the couple to the men’s and women’s meetings of their monthly meeting, which would then appoint a committee to ascertain the clearness of the parties from other engagements and the consent of the couple’s parents. This Clearness Committee reported back to the Monthly Meeting, which then appointed two men and two women to oversee the marriage. Although the language of the advices about marriage was mild (“affectionately advised”, “in motherly love”), not following them could result in disownment. The concern about marriage outside the Religious Society of Friends was mitigated over time,

from a warning about possible disownment in 1843 to the decision that the Monthly Meeting could decide whether to permit a mixed marriage in 1856. Like most weddings in the United States at this time, the ceremony itself was simple, embedded in a meeting for worship (but not on Sunday). For Quakers, who generally did not proselytize or convert members, the meeting's survival depended on the survival of family. Birthright membership started in 1737. Quaker belief suggested that children were born with the Light Within and that, if raised within an atmosphere of “holy conversation,” would likely become “vessels of the truth." This view meant that correct child-rearing practices were key and moderation was the major theme of advices on raising children.

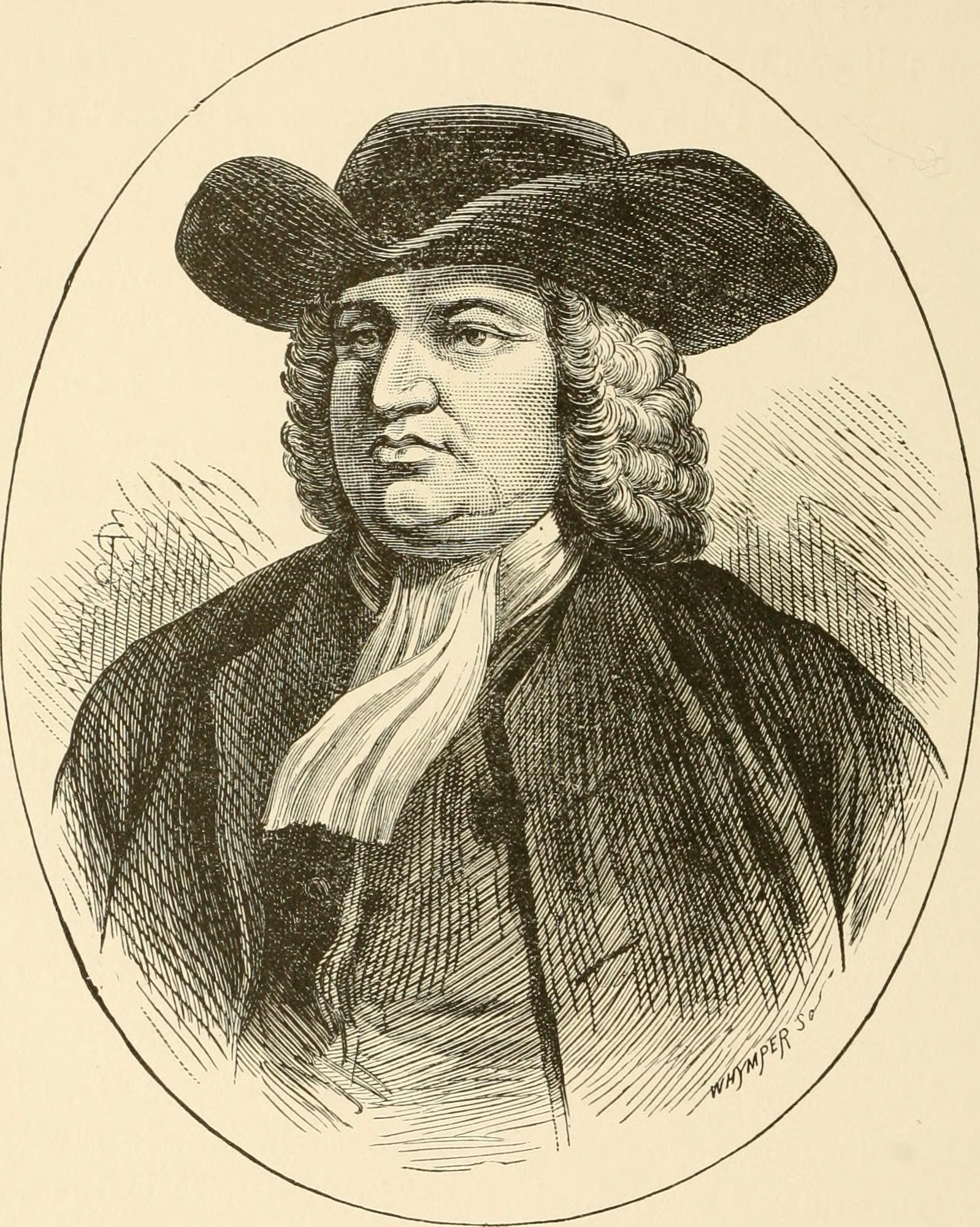

William Penn told his fellow Quakers: “if God give you children, Love them with Wisdom, Correct them with Affection".

He further advised parents to “Never strike in passion, and suit the correction to the age as well as the fault. Punish them more by understanding than the rod... rather than an angry countenance have a grieved one." Parents were expected to educate their children by acting as models of patience, humility, simplicity, sobriety, and self-denial, although worship, through silence, Bible-quoting, prayers and the testimonies, was also an effective method for helping children to recognize the difference between right and wrong.

But Penn did not rely solely on parental guidance; speaking directly to the children, he exhorted them to: “Take the advice of godly parents, guardians and Friends--submit to their reasonable requirements with cheerfulness...They watched over you and took care of you...". Even though an 1867 catalogue of Friends' books did not include books on the nature of children, its selections demonstrate the focus on living a good life according to Quakerism. Living a good life meant living simply. Penn warned children not to wear “vain fashions, associate with libertine people, frequent taverns, waste time... No plays, horse races, music, dancing or "any vain sport and pastime”! No lotteries, wagering or other gambling! The plain style favored by adult Quakers was to be followed in dress, in toys and in decorum. Despite the restrictive nature of these rules, Quaker children are known to have played with tops, rattles, kites, boats, swings, paper dolls, hobby horses, collections, experiments, marbles, hoops and balls, read books and enjoyed candy.

From the beginning, Quaker families were expected to educate their own children in the practical arts, not to prepare them for college (which were originally established to prepare religious ministers). For girls, this meant learning to sew, spin, and cook. For boys, this meant working in the shop, garden or fields. Quaker founder George Fox supported schools that would instruct students in “whatever things were civil and useful in creation”; for Penn, the inner light was linked to a person's reason.

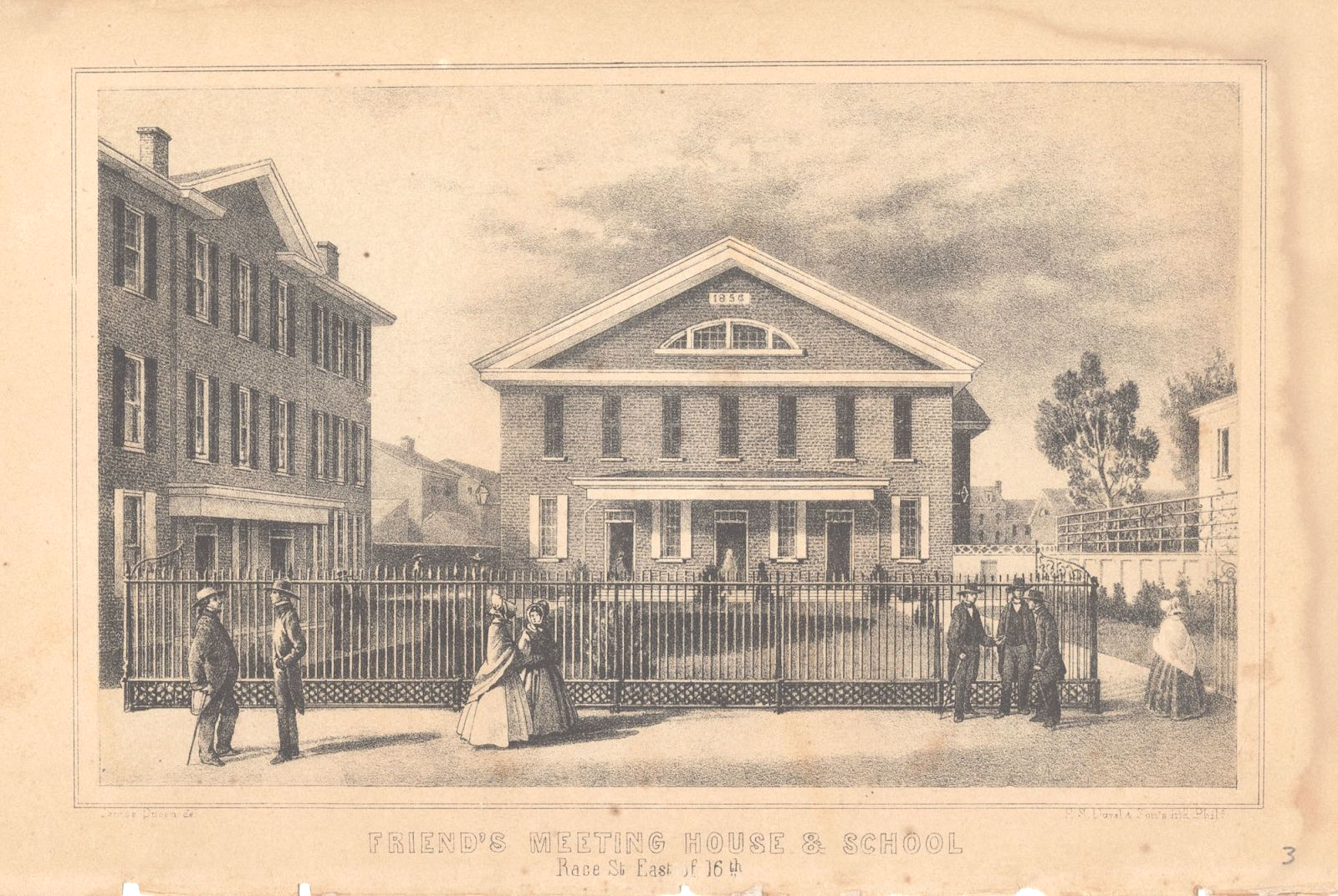

and led Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to recommend that every meeting have a school and pay a teacher. The typical reaction from monthly meetings was that distances were too great for this to work, although over the years, many Friends schools were established in the Delaware Valley. Despite legends claiming that there was an early schoolroom in the loft of the Merion meetinghouse, no evidence has been found to support this claim. In 1855, the Women’s Meeting called for the use of the back of the Merion meeting room as a schoolroom, but It is not known whether this ever happened.

By the 1820s, Quakers had transformed their goal of "moral uplift of the Quaker Poor" to the "moral uplift of all the city's children", an objective which led to the establishment of the Lower Merion Benevolent Academy by Merion Friends Meeting members. In 1850, the women’s meeting of Philadelphia acknowledged the need to educate the poor, but declared the necessity of “a religiously guarded education “ “independent of the public schools” for Quaker students. Since there were 56 Friends schools under the care of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting by that time*, it is most likely that the children of Merion Meeting attended one of those, went to a more distant Quaker boarding school

or were tutored at home, although some took advantage of the proximity of the Academy in Lower Merion and sent their children there for their schooling. In many ways, Quaker families of the early 19th century were similar to their non-Quaker neighbors, reflecting the universal focus on the nuclear family, the importance of the mother in rearing the children and a growing interest in schooling. The differences lay in the focus on the Quaker testimonies of peace and simplicity, support for practical education and a concern to protect children from the excesses of the wider world.

*In the mid-1800s, Friends' Central was a day school option for Merion Meeting’s children and Sandy Female Seminary in Darby offered boarding for girls.

Related History Pages

Related History Pages

View more