Quakers, Horses, and Carriages

Quakers, Horses, and Carriages

The Horse Sheds

Prominent structures on the hill above Montgomery Avenue where Merion Friends Meetinghouse stands, are current horse sheds that have probably been in place since the 1820s.

Although there were also stables at Merion Meeting since at least the 1790s, the current sheds represent the historical explosion of horses and carriages. The Market Revolution of the early 19th century meant a small business boom and a plethora of carriage makers, usually producing for the local market. Likewise, a higher standard of living produced demand for the convenience of wheeled vehicles. It also led to a transportation revolution, beginning with improved roads which allowed the use of wagons and carriages to transport goods and people.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 6, 2:00pm

Know Thy Neighbor

Merion Friends Meeting: A National Historic Landmark

Hidden in our Midst

REGISTER HERE to participate in this Zoom conversation

Merion Meeting Horse Sheds, built circa 1810-20.

Though in remarkably good condition for their age, both horse sheds are in need of restoration. The shed on Meeting House Lane in particular has roof damage sustained from recent storms.

Please contribute to our Preservation Campaign!

The Prominence of the Horse

Horses were key to this early market economy; even the first trains on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railway

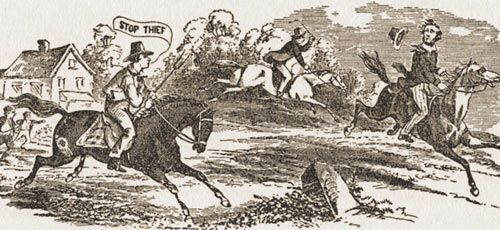

were pulled by horses! The main source of power on farms in 1840, horses became even more important with the development of turnpikes. The significance of horses in agriculture as well as transportation meant an increase in their numbers too; one historian estimates the number of horses in the United States jumped from under one million in 1800 to more than four million by 1840. From Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, all manner of merchandise was hauled by huge Conestoga wagons drawn by four and six horses. Trains of teams a mile in length were reported on their way to Philadelphia. The value of horses to American enterprise can also be seen in the scourge of horse-stealing in the early nineteenth century and in the formation of horse thieves societies (such as the Lower Merion Society for the Detection and Prosecution of Horse Thieves and the Recovery of Stolen Horses) to chase horse thieves and insure members' horses. At a time when the reward for a runaway servant or slave was 1-6 cents, the reward for recovery of a horse was $20-$80.

The Society for the Detection and Prosecution of Horse Thieves and the Recovery of Stolen Horses

Early American Vehicles

An established thoroughfare by 1740, Old Lancaster Road was the great artery of commerce for southeastern Pennsylvania. After the completion of the turnpike in 1796, it became not only the first extended paved road in the United States, but also the first toll road in the state, charging "every horse and his rider, or led horse, 1/6 of a dollar; for every sulky, chair, or chaise, with one horse and two wheels, 1/8 of a dollar; for every chariot, coach, stage wagon, phaeton, or chaise, with two horses and four wheels 1/4 of a dollar; for either of the carriages last mentioned, with 4 horses 3/8 of a dollar; for every other carriage of pleasure, under whatever name it may go, the

like sums, according to the number of wheels and horses drawing the same...". Even with this expense, passenger and freight travel on the turnpike boomed and sixty inns soon lined the road between Philadelphia and Lancaster.

Side note: it was in this era that American teamsters reversed English patterns by driving on the right side of the road!

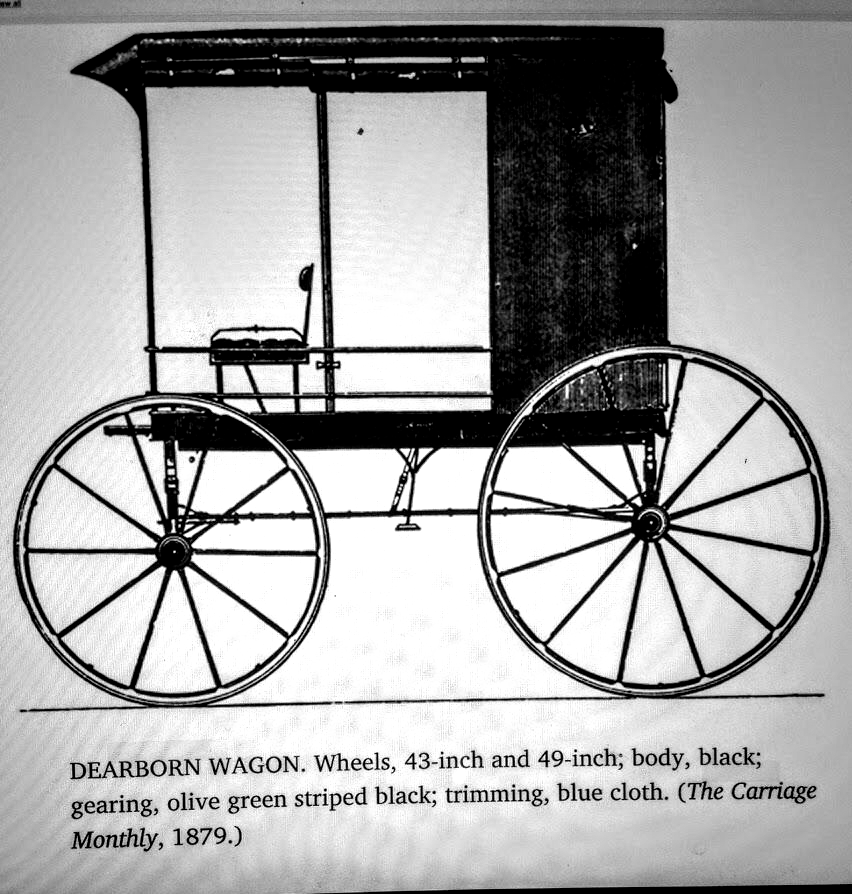

The Dearborn Wagon had two seat-boards and a standing top.

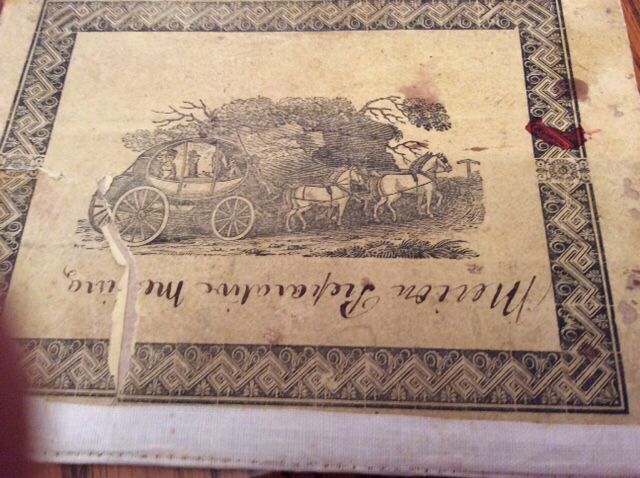

This notebook lists donations from Merion Friends Meeting members for a free school in 1809. The cover has a carriage illustration. It is actually a stagecoach for long-distance travel, which was considered luxurious because it was enclosed.

Wagons Become More Fashionable, contrary to Quaker Plainness

As the roads in the eastern United States improved, the number of carriages in use increased. In 1850, there were 1822 carriage manufacturers in the United States, producing $12 million value in carriages. In its 1860 catalogue, G.D. Cook of New York City listed 123 different varieties for sale, from queen phaetons to dog carts.

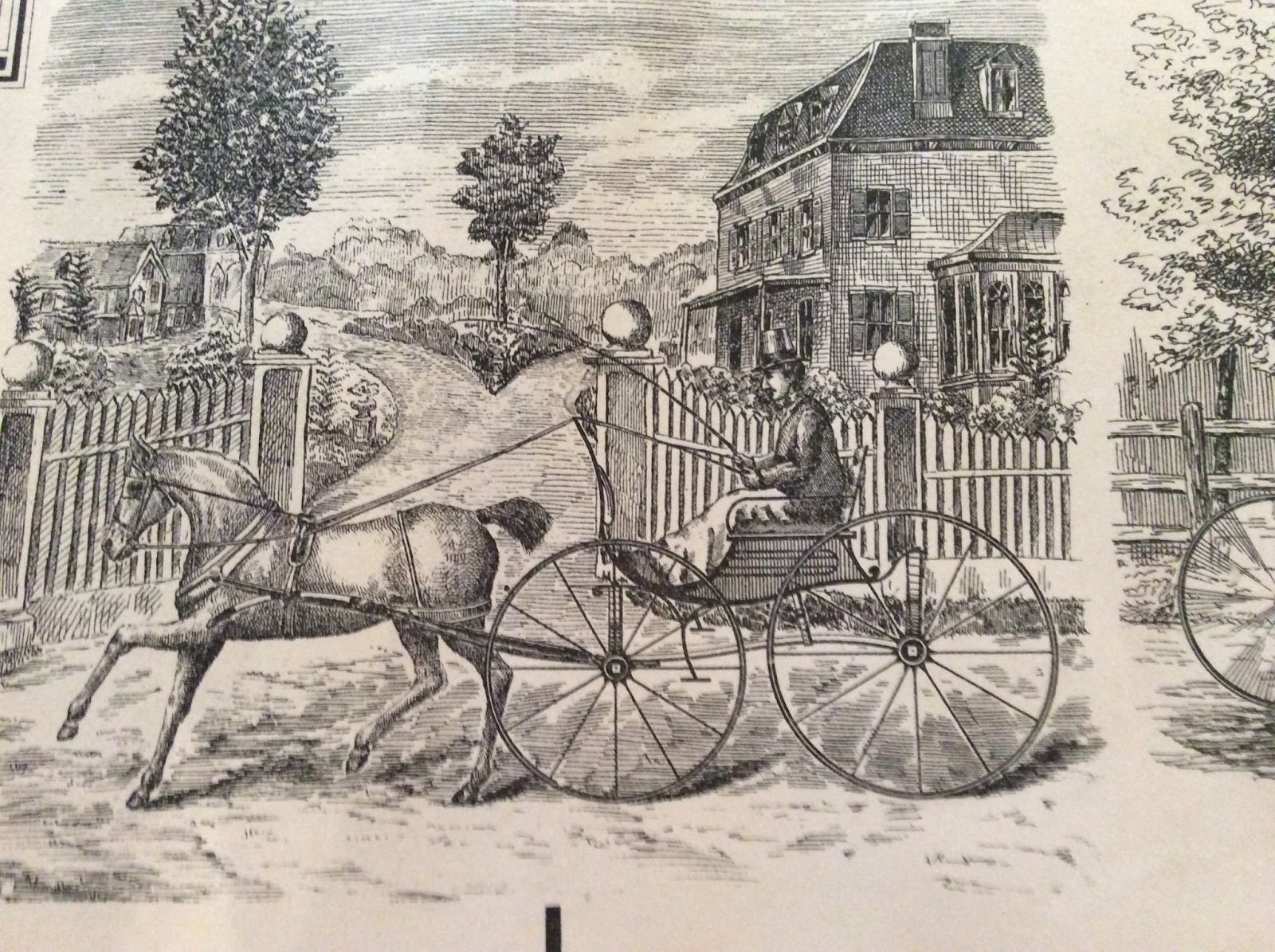

In the early nineteenth century, the most popular vehicle seemed to be the American runabout, or buggy, which was typically pulled by one or two horses and carried one or two passengers. If it had only one passenger--I.e. the driver--then it was called a sulky. The "chair" mentioned in early tax assessment books was a two wheeled vehicle on leather springs, usually without a top. After a time, these buggies acquired tops which could be thrown back and then were called gigs.

The carriage quickly became a status symbol of the rich, so for Quakers these mobile conveniences represented a potential challenge to their notions of simplicity (or Plainness). In the 1750s, carriages were in use in Philadelphia and Quakers were among those taking advantage of this mode of conveyance, but some, fearful of elite consumption, refused even to ride in one. Although the average assessment of wealth among Quakers was higher than among non-Quakers, some did not own a carriage at all. Despite the self-sacrificing frugality of Nicholas Waln and George Emlen, in 1772 Quakers constituted 1/7 of the Philadelphia population but owned 40% of the city's carriages. Gwynedd Meeting Minutes note that by 1822 its carriage sheds were accommodating 42 carriages and nine single horses. References to carriages used in rural areas around Philadelphia also occur regularly in the letters to and from a Quaker girl, Hannah Wilson,in the 1850s.

Vehicles at Merion Friends Meeting

Merion Meeting Quakers likewise used carriages in the early 19th century. Lower Merion tax records of 1833-1853 list both carriages and chairs in the assessments of Merion Meeting

members. In 1839, Silas Jones had a carriage, Edward Price had a chair and Joshua Bowman had both, although other members' tax assessments show no ownership of carriages at all. The wills of Merion Meeting members from 1825 to 1856 list chairs, Dearborn Wagons and carriages among their possessions.

Although the horse sheds nearest the General Wayne Inn may have been used for horses drawing stagecoaches, the others were built to provide cover to Merion Meeting worshippers'

horses. It is hard to know exactly how Quakers parked in the carriage sheds. Based on the evidence of chew marks on the inside back wall and on partitions within the sheds, the owners

probably unhitched the horses from the carriages and provided them with hay or oats. It is difficult to nail down the history of Quakers and carriages at this time, but there is evidence that Quakers in Lower Merion were owners of horse-drawn carriages of various styles. Since carriages were the most conspicuous status symbol of the time and "carriages and cloth" constituted "the battleground against vanity”, these Quakers would have to assuage their own consciences by purchasing the least decorated or plainest carriage available. We know that, in that era, opinions differed about the implications of the testimony on simplicity.

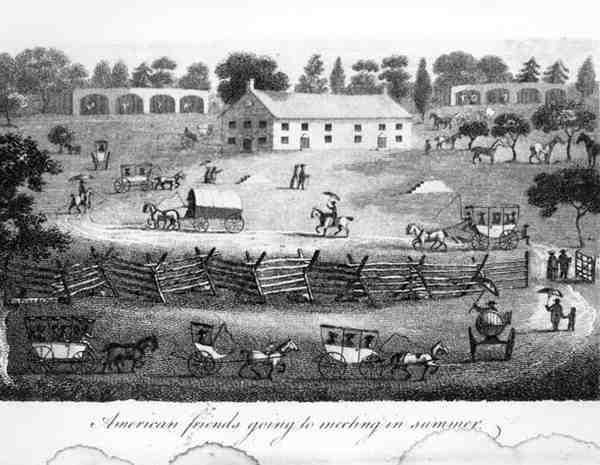

Illustration by Sutfcliff of Abington Monthly Meeting, ca. 1804 -1806. Note the variety of horse-drawn vehicles, including a Conestoga wagon, Dearborn carriage, runabout, and a depot wagon/jersey wagon/ carryall. The title is "American friends going to meeting in the summer".

Related History Pages

Related History Pages

View more