Quakers and the Antislavery Movement

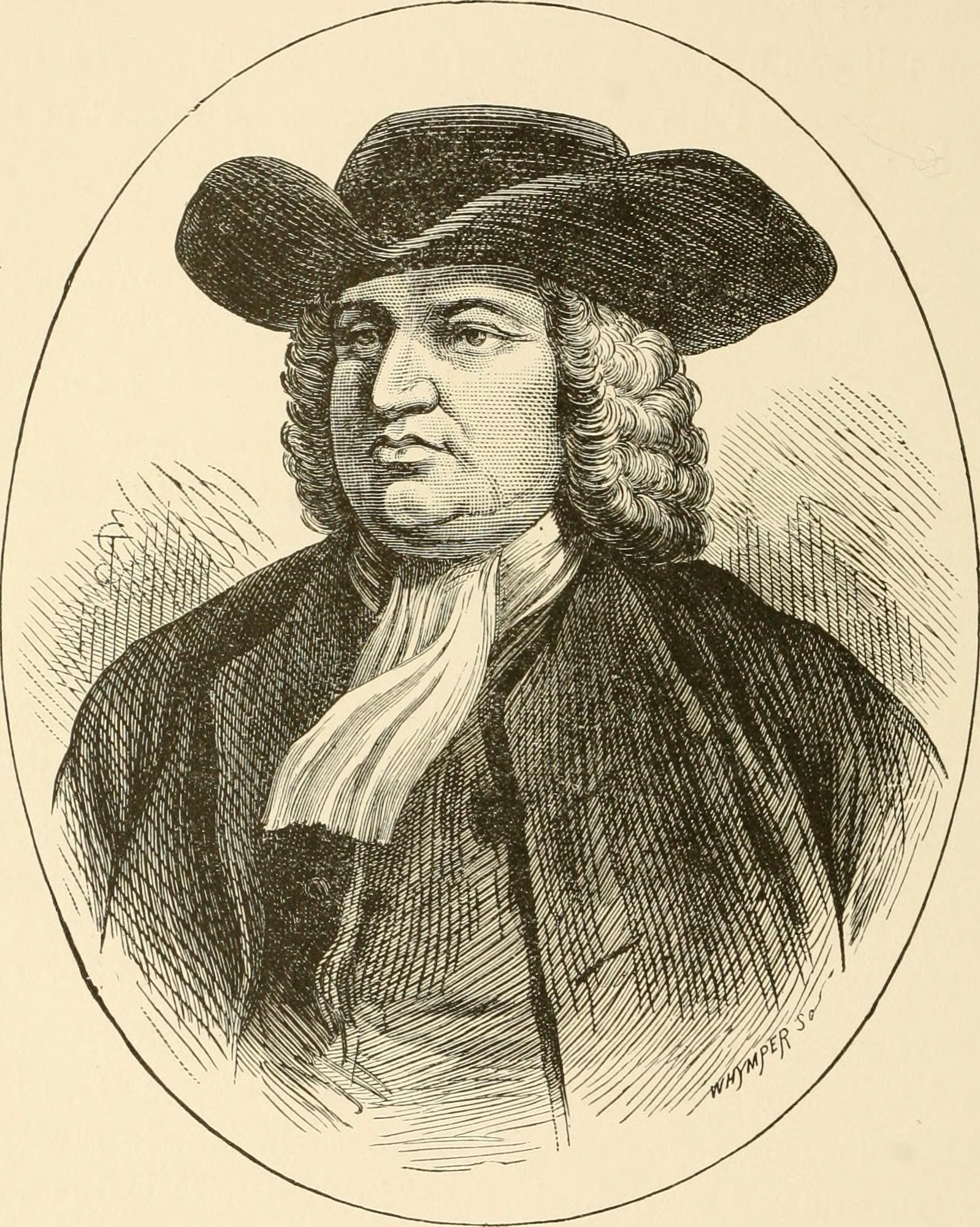

Quakers believe that there is that of God in each person and also, that to be whole spiritually, they need to live their beliefs. Friends recognized the equality of women quite early but were slower to recognize the evils of slavery. Although Quakers, including William Penn, owned slaves in the colonial era, the Religious Society of Friends was the first group to condemn slavery. In 1688, Germantown Quakers declared in writing their opposition to slavery. In the early 18th century, regional activists such as Benjamin Lay and John Woolman struck out against the institution.

In 1753, the Friends Book of Discipline stated "let us make his [the slave] cause our own" and in 1754, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting declared to its members that

"To live in ease and plenty, by the toil of those whom violence and cruelty have put in our power, is neither consistent with Christianity nor common justice."

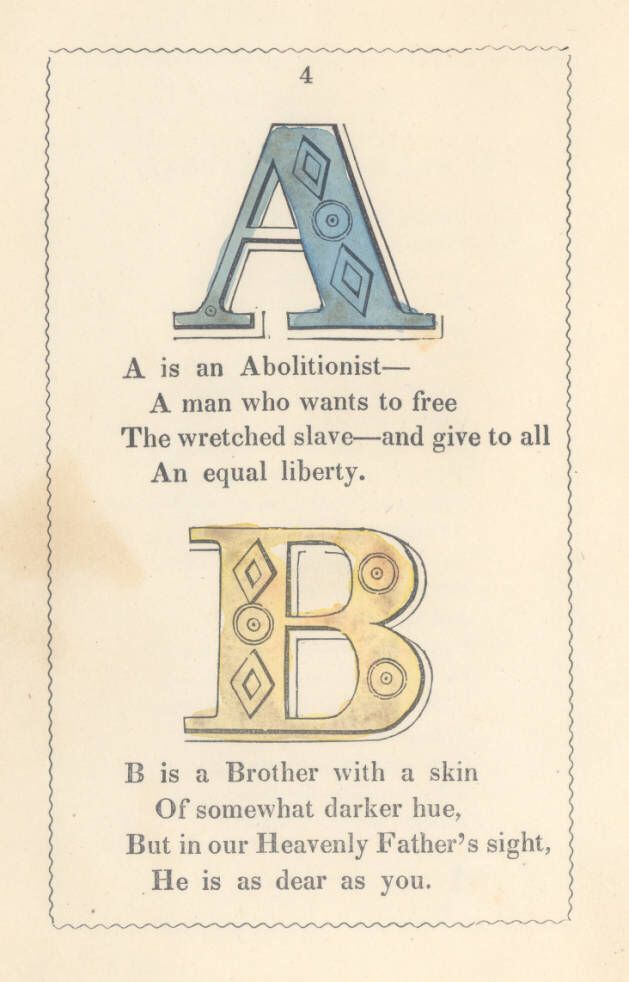

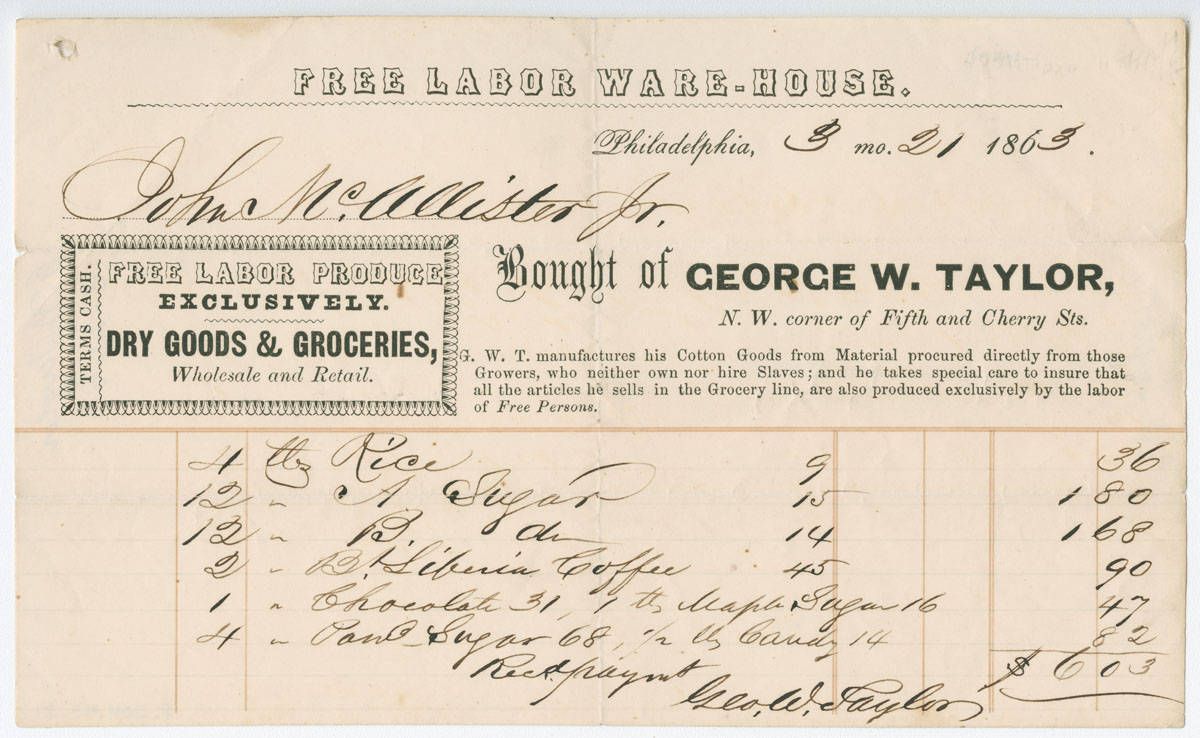

Quakers founded the Pennsylvania Abolition Society in 1784 and began to send petitions to Congress advocating the

abolition of slavery throughout the country. At the same time, they worked to end slave-owning among Quakers. By 1792, Merion Friends Meeting could declare its members free from the taint of slave ownership.

During the American Revolution, Pennsylvania had legislated the gradual end of slavery. In 1840, sixty-four slaves were counted in the census of that year. Ten years later in 1850, none were counted.

In the 19th century, support for abolition among Quakers was widespread, but there was disagreement over methods. In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison's abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator , called for the immediate end to slavery. In 1833, frustrated with the gradualist focus of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, radical abolitionists founded the American Anti-Slavery Society.

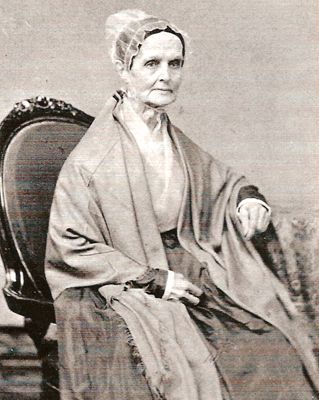

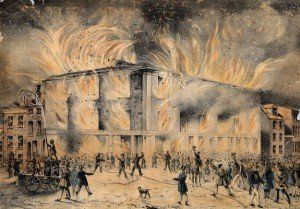

Some Quakers rejected all association with abolitionists because they thought abolitionists hated slaveholders. Friends are called to love and respect all persons and to overcome evil with good. For example, Isaac Hopper was disowned by his Meeting in 1842 and Lucretia Mott was threatened with disownment in 1842, 1847, 1848 and 1850. It became hard for radical abolitionists to find a place to meet as many Quaker Meetings said no to the use of Meetinghouses for abolitionist speeches.