Quaker Plainness in the 19th Century

For George Fox, worldly

entanglements distracted one from focus on the Inner Light. As a past Faith and Practice put it: "A life centered on God will be characterized by integrity, sincerity and simplicity." Such a life need not be cloistered but grounded in "a right ordering of priorities".

Quakers therefore made a commitment to living simply so that others may simply live: avoiding excess, living intentionally, maintaining humility of spirit. A major sin was waste--of wealth while the poor suffered or of time when work was needed. In the seventeenth century, this advice applied to housing, clothing and belongings. In 1686, one mother advised her children:

"Be careful and take heed that you do not stain the testimony of Truth that you have received, by wearing needless things and following the world's fashions in your clothing and attire, but remember how I have brought you up."

Early Quakers expected their lives to reflect their beliefs.

In this depiction of a Quaker meeting in 1840 England, there are at least three different styles of hats for men. The light, undyed beaver hat on the right of the front bench is probably a protest against slave-grown indigo.

In the 18th century, Quakers focused more on discipline within the meeting: plain speech and plain dress, simple marriages and funerals, not celebrating Christmas. Carriages and cloth

became "the battleground against vanity" and many Quakers were hostile to art, music, fiction

and drama as well. Meetinghouses were plain, without stained glass or ornamentation. There

was no organ music, no singing and the benches were hard. Plainness meant no marriages to

non-Quakers nor military service. Along with religious taboos that could lead to disownment,

there were also positive beliefs: silent worship, women's spiritual equality with men, strict

personal morality, Christ's return inwardly to teach his people.

Plain speech was one of the earliest manifestations of Quaker ideas of simplicity, substituting thee

and

thou

for you, replacing the Roman days of the week with numbers, excluding all honorary titles and refusing to swear oaths. Friends' Graves were not to include monuments as early as 1706; in 1733 Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Rules of Discipline proscribed gravestones and any set up had to be removed. This directive lasted until the end of the 19th century, although it was not consistently applied from meeting to meeting. The underlying ideology behind these conventions was a belief in the equality of all people in the eyes of God. For that reason, Quakers might still call people they do not know as Friend rather that Madam or Sir.

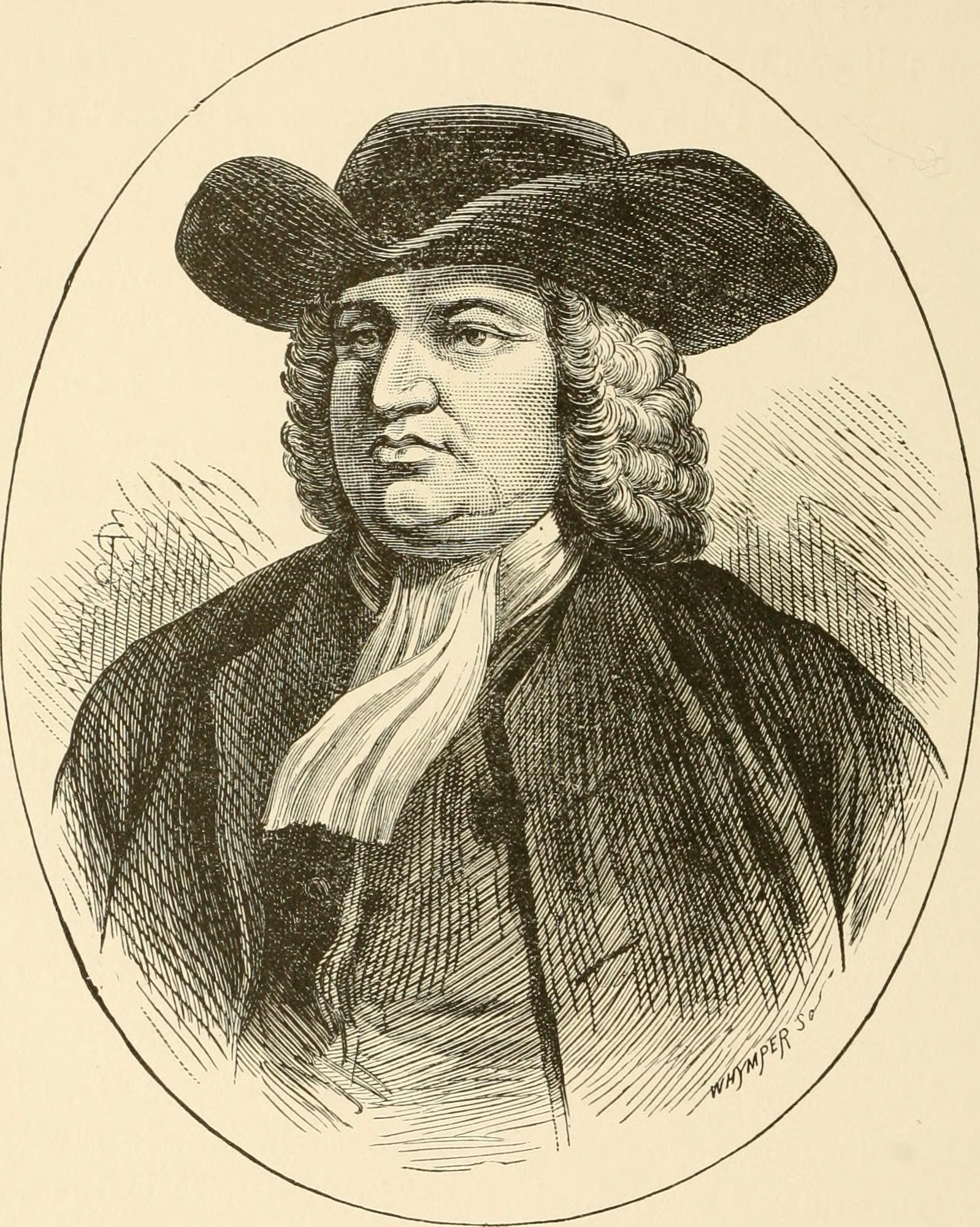

In the same way, early Quakers were concerned that dress distinguished people by class. By 1695 the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Discipline stated that Plainness required "no long-lapped sleeves or coats gathered at the sides, or Superfluous Buttons, or Broad Ribbons about their Hats, or long curled Periwiggs". In 1704, the same overseers listed the following dress ornamentation to be avoided: non-functioning buttons, scarves, large ribbons, stripe and flowered textiles. Such decorations were associated with laziness but seem generally to have been suggested rather than insisted upon. In 1797 Friends were instructed to "avoid... dress calculated more to please a vain and wanton, or proud mind, than for their real usefulness".

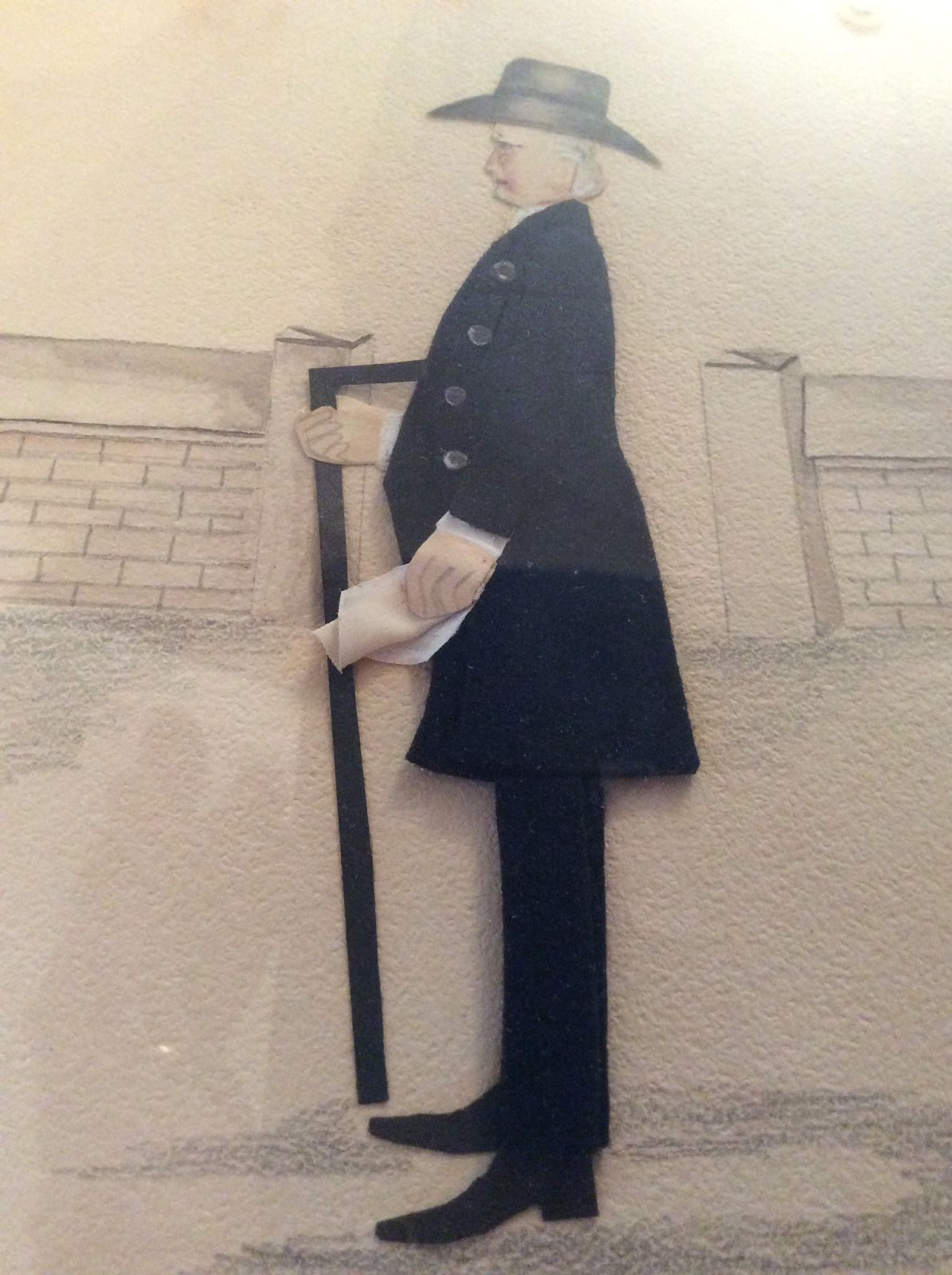

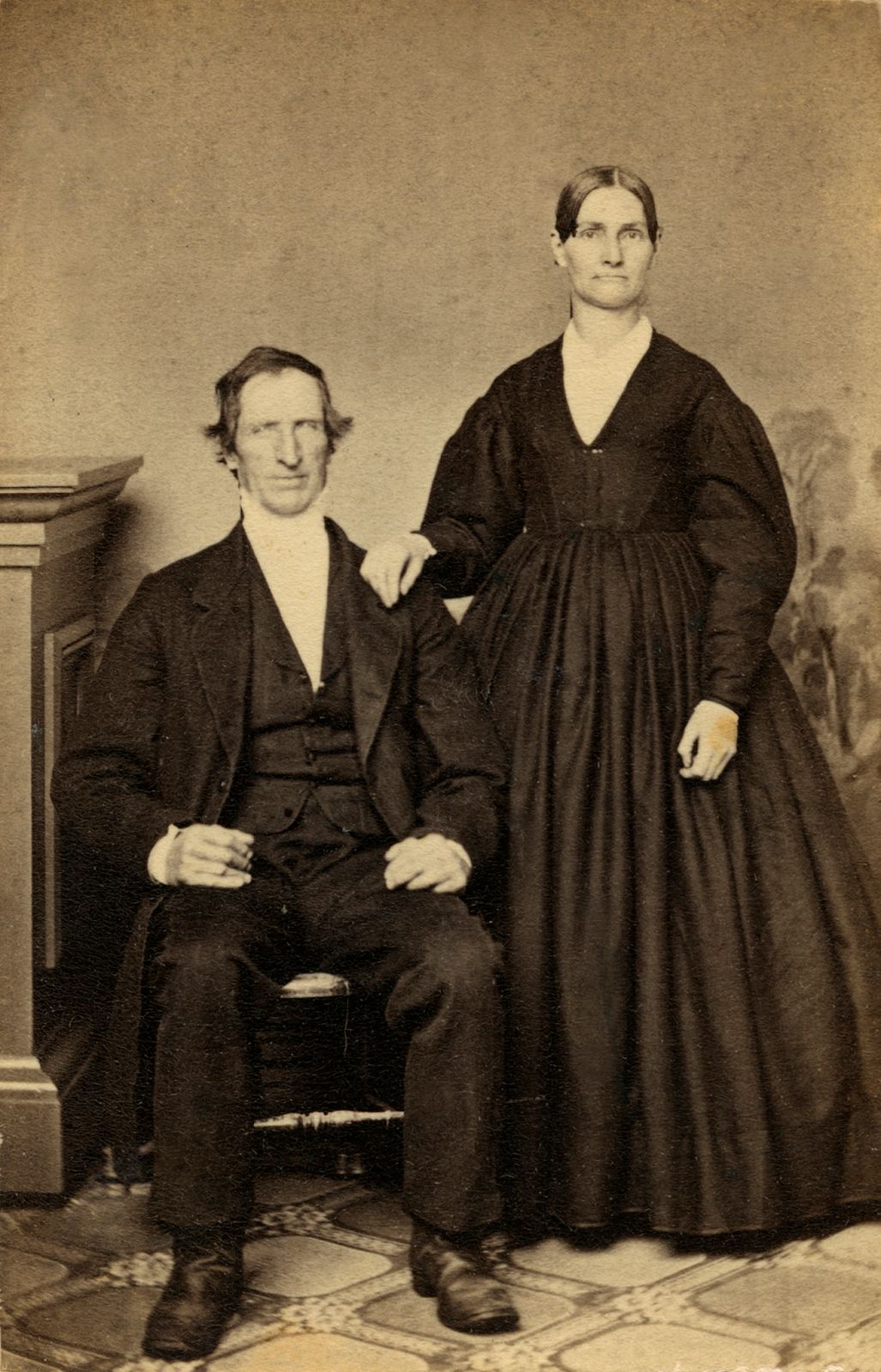

Men generally chose suits in dark colors without fashionable cuts or decorations. Children were likewise expected to live according to the norms of Plainness; in 1810 Margaret Morris exhorted her granddaughter "not to aim to live in a high style". Before 1840 the standard costume for a female Quaker was a gown, apron,square neckerchief, shawl, cap and bonnet, but in a range of plain colors and cut. A variety of interpretations were acceptable, but all avoided certain features of high style fashions. Colors may have been plain, but materials were not, silk and satin being popular fabric for dresses and bonnets. Although Quaker dress might not tell you which sect a

Friend belonged to, bonnets were distinctive and could even could identify the wearer as Baconite, Gurneyite, Hicksite or Wilburite. Clothing could be an expression of piety but Quaker

dress was never uniform.

Clothing could be an expression of piety but Quaker dress was never uniform

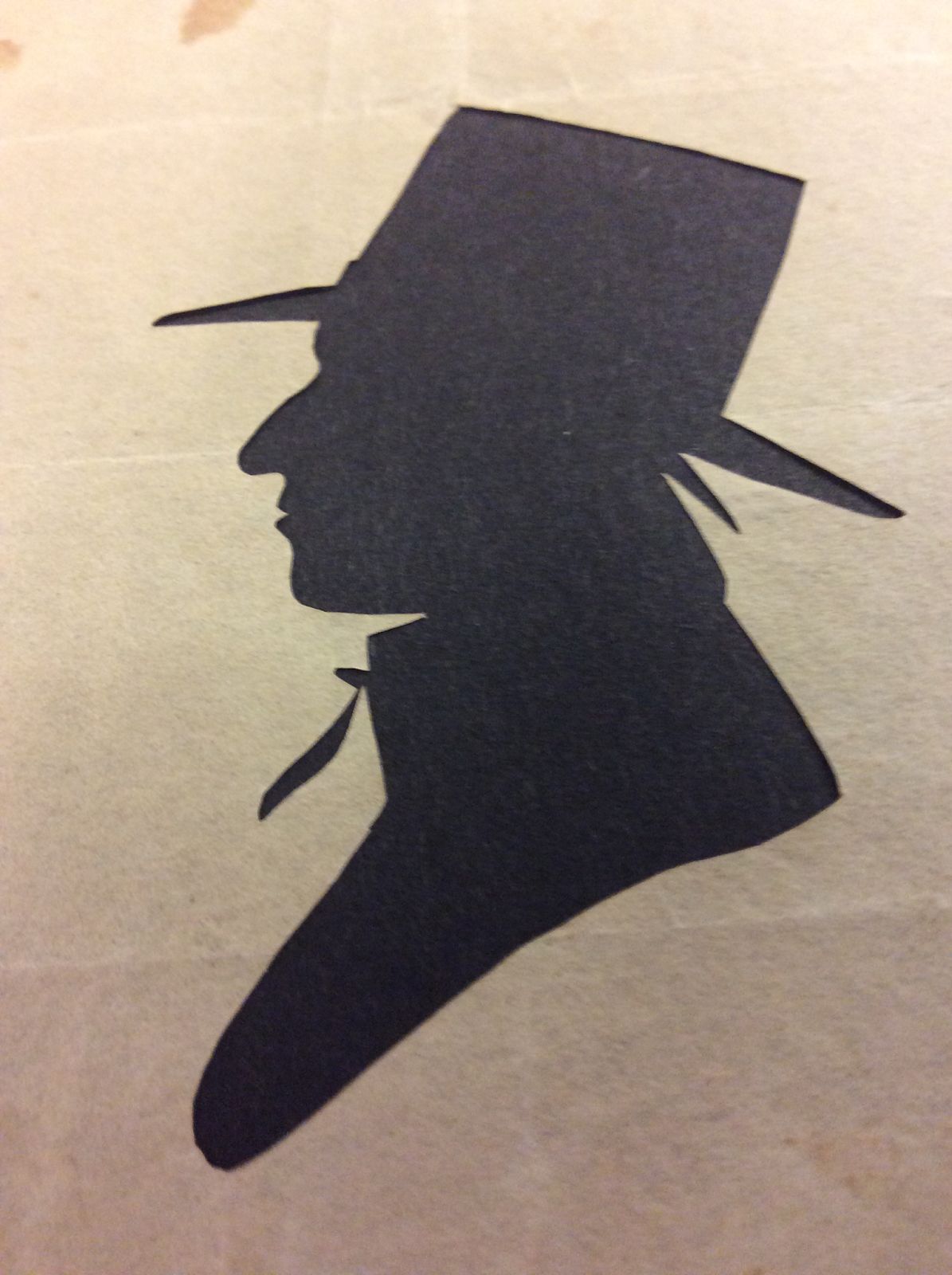

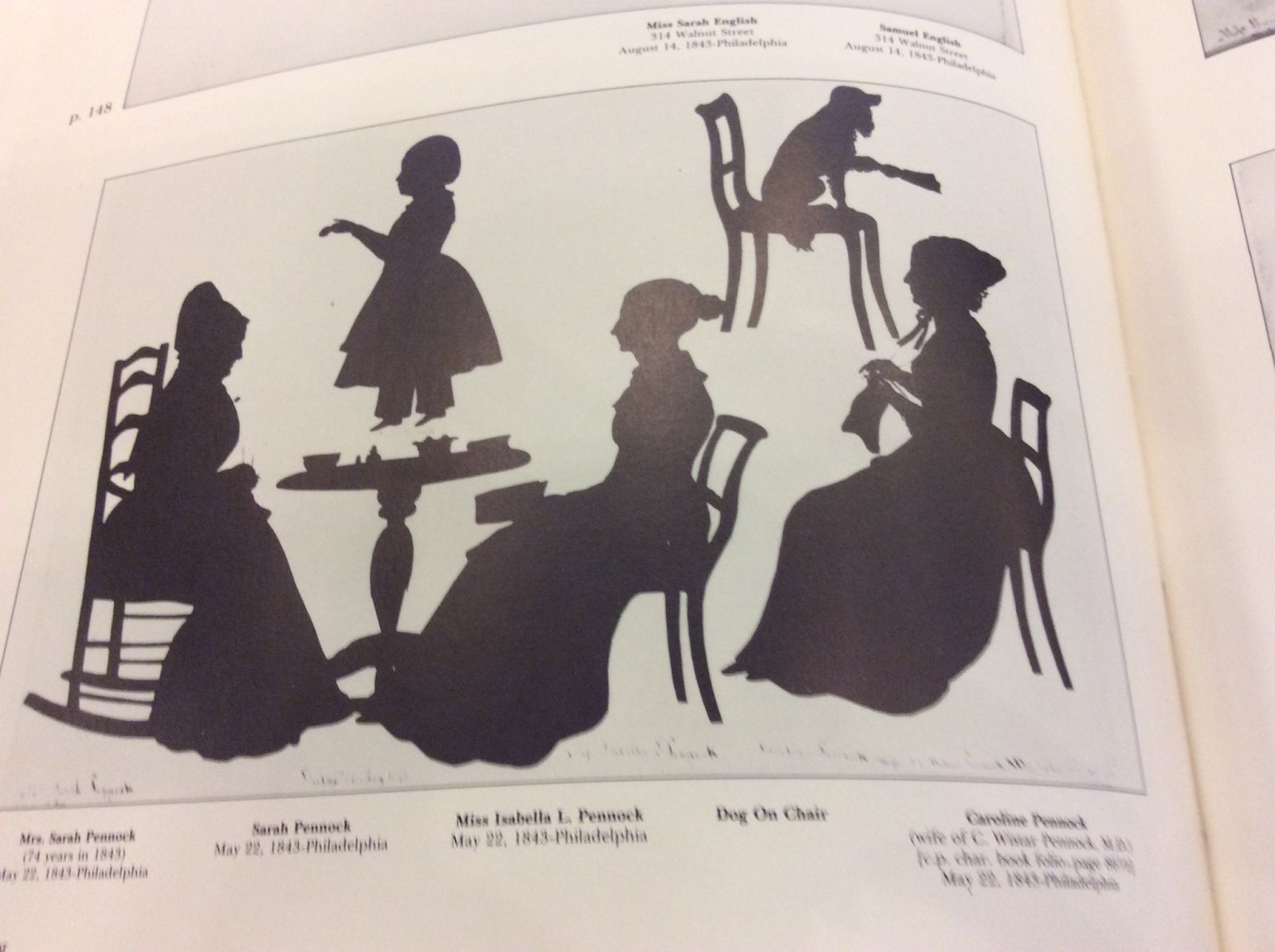

The years 1800-1830 was the era of the silhouette and many Quaker families kept family albums with the silhouettes of their members but also of well-regarded Americans, especially

anti-slavery advocates. These were popular substitutes for painted portraits until the daguerreotype was introduced in 1839.

By the 19th century, Friends' discipline over behavior increased--elders watched for those who fell asleep in meeting or strayed from simplicity or drank too much. At their business meeting on the 4th month, 5th day of 1855 (April 5) the members of Merion Preparative Meeting responded to a query from Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, declaring that their members were to be:

"generally careful to discourage the distillation or use of spirituals liquors, and to keep from attending places of diversion or the unnecessary frequenting of taverns."

Still, disownments for infractions of dress

and speech were unusual at this time and after the Hicksite-Orthodox schism in 1827, pamphlets supporting or challenging Plainness were common.

Over time, Plainness became less about group identity than about moderation and good works related to slavery, Indian rights, equality of women. Some Hicksites were more concerned with the inner light than with outward appearance. Plainness was never an absolute.

In the Midwest, Plainness disappeared by 1860, but the Hicksite-Orthodox schism delayed its demise in

Philadelphia to the 1890s or later.

At that time,

plainness was replaced by

simplicity as rejecting vain fashion in favor of decency and simplicity.

Tombstones were allowed in 1859 in New York and by 1900 plainness only survived in the style of Quaker meeting houses. Ironically, by the mid-twentieth century, Friends typically used "thee" and "thou" only for close friends and relatives.

Related History Pages

Related History Pages

View more